Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) is quickly taking the international development / global aid world by storm. According to the Institute of Development Studies it is now being used “in more than 50 countries, of which at least 15 have made CLTS official national policy”.

Traditional sanitation programs usually distribute free or subsidised concrete slabs for toilets. Initially everyone is excited, but over time the slabs end up being used for a multitude of other things such as bathrooms, cooking areas, seats, and even flower pots in one area that I worked.

CLTS was developed by Kamal Kar as an alternative to this approach. According to the CLTS Handbook:

Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) focuses on igniting a change in sanitation behaviour rather than constructing toilets. It does this through a process of social awakening that is stimulated by facilitators from within or outside the community.

What is Community-Led Total Sanitation really?

At the core it’s very simple – you show people that they’re eating each others faeces. This fact is so disgusting that the community decides to build toilets all by themselves (no subsidies required, and no need to convince them).

The process is called “triggering”, and the result is an action plan giving a date by which everyone agrees to stop defecating in the open. During the triggering you identify some particularly motivated individuals (“natural leaders”). They conduct follow-up visits to check that everyone is building toilets according to the plan. Once everyone has stopped defecating in the open the community organises a celebration.

There are many different activities that can be used to trigger the community. Here are a few of my favourites (for other ideas see the CLTS Handbook):

- Walk of shame: Tell the community members that you are visitors and you would like to learn about their village by walking around it. As you walk around, point out human faeces that you happen to walk by.

- Mapping: Get everyone to make a map of the village on the ground and stand where their house is. Then get people to mark where they defecate.

- The glass of water: Take a glass of clean water and ask if someone would be willing to drink it. Then take a hair from your head. Touch it to some of the faeces that is lying on the ground, as if it was the leg of a fly. Then touch it to the water as if the fly had landed on the water. Ask if someone would like to drink it now.

Some people have also used CLTS as inspiration for developing triggering activities on other topics, such as hand washing.

Does it work?

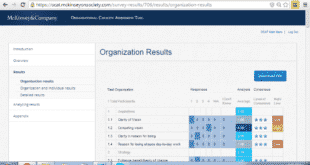

In my experience, when CLTS is done well and in the right environment, it’s one of the best ways to get immediate improvements in sanitation. In one program I worked on toilet coverage in rural villages increased from 58% to 92% in only a few months.

However, when CLTS is done poorly (as is often the case in large scale government programs) it can be very ineffective. In the same area where we were running our successful CLTS program, large numbers of government health workers had also been trained in CLTS by a donor. The result was essentially no change in latrine coverage.

The CLTS Handbook gives a few tips on environments where CLTS is most likely to work – typically small rural communities that are socially homogeneous. It also suggests environments where it is more challenging, including urban settlements, communities that are culturally diverse, or areas that have a traditional subsidy based program running.

Whether short term improvements can be sustained in the long term is also still a question that needs to be answered. WaterAid is one of the few organisations to publish a follow up study of their CLTS programs in Bangladesh, Nepal and Nigeria.

The results showed that in Bangladesh and Nepal a relatively high level of latrine coverage had been maintained in most communities (although not all) after the intervention. However, in Nigeria there were more mixed results. More long term studies are needed to determine whether CLTS actually leads to long term change.

Update: This article was updated to include information on CLTS in different environments.